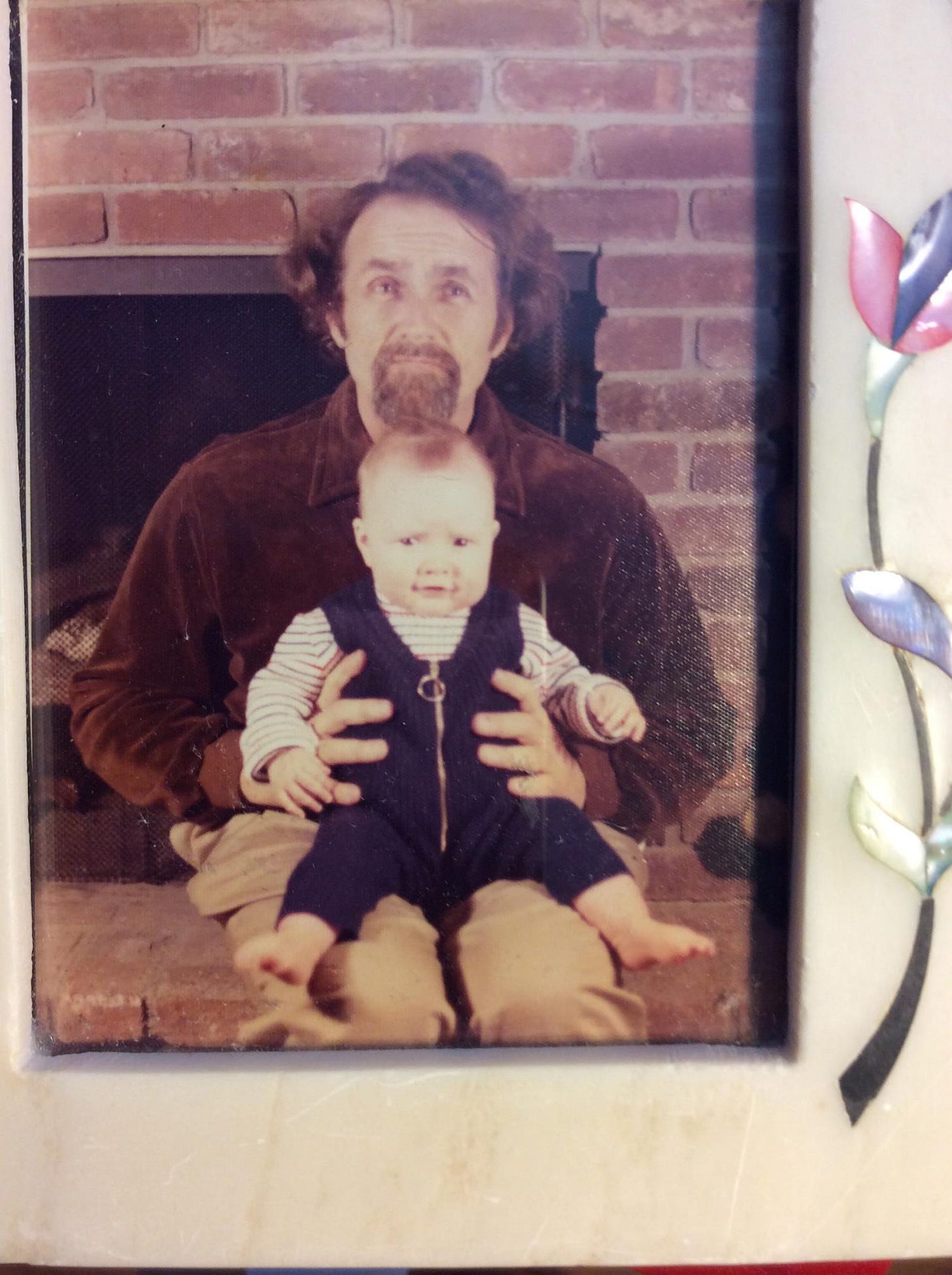

My Dad and me, late 1972

A few days after my father died, I lay in bed talking to a friend who’d lost her infant son years before. “How’d you go on?” I asked her. I’d never taken to bed with grief, and the question briefly felt quite alive for me. In those early days it felt like Dad had been the structural wall holding me up.

His name was David D. Siegel, and his favorite titles were Daddy and Professor. In his school and home offices he displayed toddler photos of me and my little sister, and didn’t switch them out as we grew up. His masterpiece, Siegel’s New York Practice, presided over us. It was a forest green legal textbook whose five editions followed me around the house as I grew up. It was beside me on the shelf in the living room where I’d read on the couch, on another shelf in the guest bedroom where I’d read in a corner swivel chair. A copy can’t possibly have lived on the shelves of my sister’s bedroom, yet I see one there, beside First Year Latin. New York Practice had as many pages as the Bible, and law students and attorneys used to call refer to it that way. I remember a fancy luncheon in the 1980s where a man leaned down to ask me: “Did you know that your father is God?”

I did know that, because I lived in the two-hundred-acre kingdom where his will was done. Dad had decreed that we should have built for us a big, weird house sited on the clear, Green River at the center of four corn fields. It should have flat roofs and no right angles, and there was to be an intercom system with speakers in every room, including bathrooms. Three was the correct number of staircases, with two being spiral, and housed in turrets, and the third straight and normal but leading nowhere, “just for show,” like Tevye sings in “If I Were a Rich Man.” To assist in the enforcement of another decree, this one against unpleasant thudding sounds, he had the desk in his home office covered in carpeting. To assist in the thwarting of would-be busybodies, he'd lettered the labels on his office’s 25 filing cabinets using the Cyrillic alphabet.

I, a would-be busybody, was clever enough to figure out which drawer housed information about me, but I never touched its handle, because I thought the exotic letters were electrified like a fence. Another of Dad’s decrees is still influencing my behavior. I’ll be 53 soon but I still feel pulled to go to bed early because Dad told Mom that we were to be settled in our rooms no later than eight pm so he could get to his writing in peace.

Our four-person family gathered nightly at the dinner table/ Dad’s home classroom, and the title of the course he most frequently taught there might have been called “English, via Music Written Before 1900.” Class was in session when something put him in mind of a favorite song. At that point he’d incline his body sharply toward us and open wide his eyes, signals that conveyed, “Time to learn something important for a change, girls!” He'd put up a thick index finger like a conductor’s baton and bare his teeth, the better to demonstrate the syllabic distinctions.

In Gilbert and Sullivan’s patter song “I am the Very Model of a Modern Major General” he found a tool for improving our sloppy enunciation.

I am the very model of a modern major general

I’ve information vegetable, animal and mineral.

I know the kings of English and I quote the fights historical,

from Marathon to Waterloo, in order categorical….

Dad’s favorite game was, “Keep a straight face while I count to three,” and he applied its dollar bill incentive to the challenge of producing the first verse of “A Modern Major General.” But I was easily discouraged and gave up trying after one or two failed attempts. I also could never kept a straight face and Dad found my repeated failures in that game, year after year, delightful, but there I lost intentionally, so as to delight him.

Dad singled out Julia Ward Howe’s lyrics in the second verse of “Battlehymn of the Republic” as an exemplar of simple language used to excellent effect:

I have seen Him in the watch-fires of a hundred circling camps,

They have builded Him an altar in the evening dews and damps;

I can read his righteous sentence by the dim and flaring lamps…

His day is marching on!

Up and down the thick finger went, in and out and up and down went his lips over and around his teeth, marking out each sharp syllable. On the immediate heels of “marching on” he inserted his urgent analysis.

“Do you hear it? Do you hear how ‘camps,’ ‘damps,’ and ‘lamps’ mimic the rhythm of a marching army?”

“Yes, Dad,” I’d say.

If my assurance convinced him, his eyes would release their professorial hold and sparkle with pleasure.

“Now!” he’d announce. “Isn’t that remarkable?”

“Yes, Dad, it’s remarkable,” I’d agree.

As a young child I loved to be important enough to keep Dad away from his important work, and savored our God-disciple dynamic. But as I reached adolescence I grew more skeptical. Around that time he did expand his curriculum to include historical quotes and anecdotes, but I could see that he had a finite number of lessons. He was not God, in other words, but a man who repeated himself.

If he was reminded of, say, drunkenness, and leaned eagerly forward to ask, “Have I told you what Winston Churchill once said to Lady Astor at a party?” the only correct answer was, “No, I don’t think so.” If instead I said, in a condescending tone, “Yup, you told me that one already,” his eyes would deaden and he’d make to get up from the table.

“Well, then, I wouldn’t dream of boring you,” he’d say.

This — the atmospheric shift from warm to cold— would scare me. As he retreated, I’d advance.

“No, no! I’d like to hear it again, Dad.”

He’d retreat further, setting his mouth into a hard, humorless line.

I’d ramp up my protestations.

“Dad, please, tell me the story again!”

I could no sooner extract myself from my chair at the dinner table when Dad was teaching than I could touch an electrified filing cabinet or play loud music in my room after 8 pm. Maybe other teenagers had the gumption to walk away from their parent, or to sneak out of the house, or to establish interests and skills that they’d landed on independently, rebelliously. I was not such a teenager. My parents’ demands and summons, issued via the house’s ubiquitous intercom system, could take me at any moment away from the confused, inchoate world of Sheela, back into the regimented, inflexible world of Mom and Dad.

Going away to college did not change everything, but it did provide what felt like my first important life choice.

I got to choose which language I wanted to learn.

Latin and French I’d found to be mostly landmines, opportunities only for failing to achieve an A. But I got an A in Italian class every semester of my college career, because an A, in that case, represented love. I didn’t understand why my fellow students were not enamored of the musical sounds emanating from our professor. I’d never before experienced self-discovery through a school subject. Italian was an open door onto a new me, a person who I, and I alone, had the power to access. A person who, through the power of this language, found a whole new country waiting to be explored.

Italian is where my relationship with my Dad shifted again.

As a French major at Brooklyn College he’d used the 23rd Psalm —The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want — to practice not only his French, but also Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian pronunciation. So when I came home for a weekend during that first college semester and announced at the dinner table that I was learning Italian, Dad inaugurated a new class: “How to Correctly Pronounce the King James Version of Psalm 23.” He’d forgotten some of the words, so we spent most of our class time on what he said was his favorite phrase.

La mia coppa trabocca.

My cup runneth over.

I was still a beginner then, and couldn’t get the Italian right. I said the “o” in “coppa” and “trabocca” like the hard, blunt English “oh” instead of the soft and sublime Italian “o,” which requires a strenuous pursing of the lips.

“See, Sheela, you have to stretch your mouth,” Dad would say, extending his lips and rounding them into a big, embarrassing O. “You have to exaggerate the movement.”

“Coppa” and “trabocca” made me feel ridiculous, and while I knew other people’s correct and incorrect pronunciation when I heard it, I was not yet ready to work hard at mastering my own. Dad worked so hard with me, enlisting his eyes, both index fingers and an O-shaped mouth to persuade me, “This matters!”

It wasn’t long before my pronunciation improved. It wasn’t long, in fact, before I was living and working in Italy, where I was often taken for a native speaker. I started teaching Italian after I returned home, so as not to unlearn it.

I’ll start “Italian Pronunciation Lesson #1” with my beleaguered favorite word. The first three letters of “tagliatelle” do not sound like “tag.” In Italian the letters “gli” make a smooth sound which approximates the double L in the English word “brilliant.” (Dad taught me that trick.) It’s quite unnatural for English speakers, which makes it one of the most difficult Italian pronunciation challenges. A similar rule applies to the archaic word “benignità,” which means kindness but stands in for “mercy” in the penultimate line of the King James version of Psalm 23, as in:

Certo, beni e benignità m’accompagneranno tutti i giorni della mia vita

(Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life)

The accent on the last syllable of “benignità” tells you to stress that syllable. The first two syllables do not begin with “benig.” The “gn” is smooth. It draws the tongue to the front of the hard palette, just behind the teeth, and inspires it to unfold gently off. There is no perfect English equivalent of the Italian “gn.” It is similar to the “ny” in “canyon” or the “n” in “onion,” but it is not the same. My students get frustrated by this, as they do with “gli,” but I long ago mastered the sounds, and now I especially love the “gn” in “benignità.” I believe the word is an onomatopoeia exuding kindness and mercy.

My mind is inclined toward extinct Italian poetry, and my extinct father led it toward that inclination.

______________________

Dad’s memorial service included, among other things, a fond statement from the Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, a trio performance of “Sabbath Prayer” from Fiddler on the Roof , “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” sung rousingly by two hundred people, and four renditions of the 23rd Psalm. Friends and relatives recited the English, Spanish and French, and I recited the Italian.

Though my heart caught on our favorite words --

Tu ungi il mio capo con olio; la mia coppa trabocca.

(You anointeth my head with oil; my cup overflows.) --

I recovered for a beautiful finish.

Certo, beni e benignità m’accompagneranno tutti i giorni della mia vita

(Surely goodness and mercy will follow me all the days of my life)

Ed io abiterò nella casa dell’Eterno per lunghi giorni.

(And I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.)

I dwelt a long time in the house of my father, and toward the end of my time there, at the end of our Psalmo 23 lesson, Dad leaned back in his chair, and, pleased with my progress, sighed. He interlaced his hands on his big, soft belly and asked, “Now, isn’t that beautiful?”

“Yes, Dad. It is so, so beautiful.”

I wish I'd met him!

Sheela: This is such a loving tribute to your Daddy and the beautiful yet complex relationship you shared. I loved reading this piece and it brought tears to my eyes as I remembered my own complex father/daughter relationship.